Have you ever wondered why your body instinctively reacts to stress in ways that seem beyond your control? Why you might lash out, shut down, or try to please everyone? These automatic responses are often tied to trauma, and understanding them is the first step toward breaking free from survival mode.

What are trauma responses?

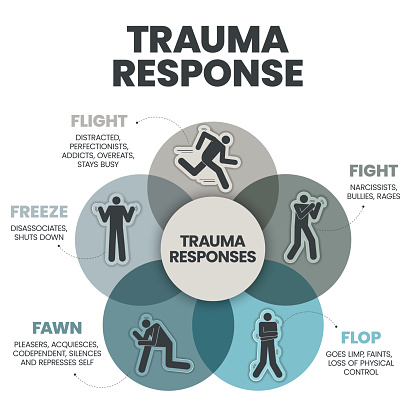

Trauma responses are automatic reactions that our bodies and minds engage in when we face danger or intense stress. These responses are deeply rooted in our survival instincts and are designed to protect us from harm. Trauma responses fall into four primary categories: fight, flight, freeze, fawn and flop. Each response is triggered when the brain perceives a threat, and they are meant to help us either confront, escape, endure, or appease danger.

How Trauma Responses Develop?

Trauma responses develop as a result of experiencing or witnessing traumatic events. These events can include anything from violence, accidents, abuse, or neglect to natural disasters. When the brain detects a threat, the amygdala (the part of the brain responsible for fear processing) sends a signal to the nervous system to activate the body’s fight-or-flight response. For those with trauma, especially those who experience chronic or repeated trauma, these survival mechanisms become hardwired into daily life.

Over time, the body and mind may become stuck in a heightened state of alertness, even when no immediate danger exists. This is why people who have endured trauma may experience one or more of these responses long after the event is over. Trauma responses become automatic, even when they are no longer helpful, and can significantly impact relationships, decision-making, and well-being. Variances in childhood abuse or neglect patterns, birth order, and genetics can influence how individuals develop their unique 5F survival strategy. Over time, individuals may gravitate toward one primary survival strategy based on these influencing factors.

healthy 5f responses

A healthy 5F (fight, flight, freeze, fawn, flop) response reflects an individual’s ability to access all survival strategies in an adaptive and balanced way, depending on the situation. This flexibility allows them to respond appropriately to danger or stress, without becoming stuck in any one reaction. Let’s explore how each of these healthy responses might look:

1. Fight (Healthy Boundaries and Assertiveness)

In a healthy individual, the fight response is not about aggression or domination. Instead, it reflects a person’s ability to set boundaries and assert themselves confidently when necessary. They can stand up for their rights, defend their beliefs, and protect themselves or others without excessive anger or hostility.

- Example: A person calmly but firmly tells a colleague that their behavior is inappropriate and expresses how they want to be treated.

2. Flight (Constructive Disengagement)

A healthy flight response allows someone to recognize when a situation is becoming dangerous or counterproductive and to withdraw or retreat in a way that preserves their well-being. This is not avoidance, but a tactical retreat from unnecessary conflict or overwhelming stress.

- Example: During a heated argument, someone might excuse themselves to take a break and cool down, ensuring that they return to the conversation with clarity.

3. Freeze (Pause and Evaluate)

A balanced freeze response involves the ability to pause and assess a threatening situation before making a decision. Rather than getting stuck in paralysis, a healthy freeze response helps an individual to reflect, gather information, and decide whether to take action, retreat, or cooperate.

- Example: When faced with a sudden job loss, a person might take some time to process their emotions and evaluate their next steps, rather than rushing into a panicked decision or giving up.

4. Fawn (Empathy without Losing Self)

When healthy, the fawn response allows someone to use empathy, cooperation, and diplomacy to de-escalate situations or build rapport without sacrificing their own needs. It’s about listening and accommodating others while still maintaining personal boundaries and self-worth.

- Example: A person helps resolve a team conflict by being compassionate and understanding toward all parties, but also ensures that their own concerns are heard and addressed.

5. Flop (Appropriate Surrender and Letting Go)

The flop response, when healthy, involves knowing when to surrender control and let go of the struggle, particularly in situations where resistance is futile. It’s not about giving up entirely, but recognizing when it’s time to stop fighting and allow oneself to rest or trust others.

- Example: Someone accepts help from others during a time of crisis, allowing themselves to be vulnerable and cared for, rather than struggling to do everything alone.

While these responses can protect us in real danger, trauma can cause us to overuse them in ways that harm us rather than help us.

Maladaptive 5f responses

Traumatized individuals often learn to survive by overusing one or two 5F responses. Trauma rewires the brain to be hyper-focused on survival, leading to an over-reliance on one or more of these responses, even in situations that don’t requires it. In traumatized individuals, the 5F survival responses become maladaptive, often leading to chronic stress and dysfunctional behaviours. This can result in a pattern of overuse, where individuals react in ways that were once necessary for survival but are no longer helpful in everyday life. This influences our ability to relax and creates a narrow and strapped experience of life.

Here’s how each of the 5F responses typically operates in people with trauma:

1. Fight (chronic agression or defensivness)

In a traumatized person, the fight response often manifests as excessive anger, aggression, or hyper-defensiveness. They feel the need to confront perceived threats aggressively, whether through verbal or physical means. For them, anger becomes a defense mechanism to maintain control or protect themselves. While the fight response is necessary in some situations, overusing it leads to excessive conflict, outbursts of anger, a constant need to control others and a need for dominance in everyday situations. This overactivation of the fight response stems from feeling unsafe and needing to assert power over others or their environment to regain a sense of control.

- Signs: Anger issues, controlling behavior, confrontational attitudes, overprotectiveness, frequent arguments.

- Example: A person might lash out at a loved one for small disagreements, perceiving criticism as a threat to their emotional safety.

2. Flight (Chronic Avoidance)

When the flight response is overused, trauma survivors may become overly focused on avoiding situations or people that trigger discomfort or anxiety. This can lead to chronic avoidance, where they run away from any situation that feels threatening, even if it’s safe or necessary for growth. This might manifest as a compulsion to stay busy and develop the need for perfectionism, using productivity to escape their emotions.

- Example: Someone might avoid close relationships entirely, fearing rejection or conflict, and isolate themselves to feel safer.

3. Freeze (Paralysis or Dissociation)

The freeze response, in a traumatized individual, often manifests as paralysis or dissociation. They may become stuck, unable to act or make decisions, feeling mentally and emotionally frozen in the face of stress. Dissociation, a common trauma response, can involve a sense of detachment from oneself or reality as a way to escape overwhelming emotions or memories.

- Example: A person may find it difficult to make even simple decisions, or they may mentally “shut down” during stressful conversations or situations, feeling numb or detached.

4. Fawn (People-Pleasing and Self-Neglect)

The fawn response becomes maladaptive in trauma survivors when it leads to extreme people-pleasing behaviors. Traumatized individuals may habitually put other’s needs before their own, often at the expense of their own well-being. This response often stems from a deep fear of abandonment or rejection and the belief that pleasing others is the only way to stay safe or loved.

- Example: A person might constantly sacrifice their own needs and opinions to make others happy, even in toxic or abusive relationships.

5. Flop (Helplessness and Collapse)

The “flop” response is a lesser-known survival reaction in the spectrum of trauma responses. It often involves a complete collapse of physical or emotional resistance, where the body essentially “shuts down” in the face of overwhelming stress or danger. This response can manifest as fainting, feeling physically paralyzed, or even experiencing non-epileptic psychogenic seizures (NEPS). NEPS are episodes that resemble seizures but are not caused by electrical disturbances in the brain, they are typically triggered by stress or emotional overwhelm rather than neurological issues. The flop response in trauma survivors can also lead to feelings of helplessness or complete surrender, even in situations where they have control. They may feel unable to stand up for themselves or believe that resistance or action is futile, leading them to “give up” easily. This learned helplessness can create a cycle of passive surrender to abuse, neglect, or unhealthy patterns in life.

- Example: Someone might stay in an abusive relationship because they believe they don’t have the power to leave or improve their situation.

- Example 2: A person experiencing a non-epileptic psychogenic seizure (NEPS) during a highly stressful situation. Imagine someone with a history of trauma being in an overwhelming confrontation at work. As the pressure builds, their body may shut down because their brain perceives the situation as inescapable or too overwhelming. Instead of reacting with anger (fight), leaving the situation (flight), or trying to appease the other person (fawn), the individual suddenly collapses or experiences seizure-like symptoms.

Why Do These Responses Become Maladaptive?

Trauma survivors’ brains become wired for survival, often stuck in a constant state of alert, perceiving threats everywhere, even in non-threatening environments. Over time, the 5F responses become automatic defense mechanisms that no longer serve the individual in healthy ways. Instead of responding appropriately to danger, they may find themselves constantly reacting in these maladaptive ways, even when they’re safe.

- Chronic Hypervigilance: People with trauma often live in a state of hypervigilance, always scanning for danger. This can overactivate one or more of the 5F responses, causing them to react strongly to situations that wouldn’t provoke the same reaction in others.

- Conditioning and Survival Mode: In early trauma, these responses were likely the only means of surviving unsafe environments. As a result, they become ingrained and overused, even when the person is no longer in danger.

- Lack of Flexibility: Trauma often leads to a lack of flexibility in how these responses are used. Instead of being able to move between fight, flight, freeze, fawn, or flop based on the situation, survivors may get stuck in one dominant response that shapes how they react to all challenges.

Healing and Rebalancing the 5F Responses

In trauma recovery, the goal is to regain balance and flexibility in how these 5F responses are used. Therapy, particularly trauma-informed approaches, can help individuals recognize their default survival responses and learn healthier coping mechanisms. Healing involves:

- Increasing Self-Awareness: Understanding which survival response is dominant can help individuals begin to shift their reactions.

- Mindfulness and Grounding: Mindfulness techniques can help trauma survivors stay present and grounded, reducing automatic fight, flight, freeze, fawn, or flop reactions.

- Building Healthy Boundaries: Relearning how to assert boundaries (fight), retreat when needed (flight), reflect (freeze), compromise without losing oneself (fawn), and let go when appropriate (flop) is key to a more balanced response to stress and danger.

Through this process, individuals can learn to reclaim control over their responses, allowing them to navigate life with more resilience, confidence, and peace.

If you recognize these patterns in yourself, know that healing is possible. Consider working with a trauma-informed therapist who can guide you in regaining control over your survival responses and helping you live a more balanced, resilient life.

References

- Herman, J. L. (1997).Trauma and Recovery: The Aftermath of Violence – From Domestic Abuse to Political Terror. Basic Books.

- Levine, P. A. (1997).Waking the Tiger: Healing Trauma: The Innate Capacity to Transform Overwhelming Experiences. North Atlantic Books.

- Van der Kolk, B. A. (2014).The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, Body in the Healing of Trauma. Viking.

- Walker, P. (2013). From Surviving to Thriving: A Guide for Healing Trauma.

- Fisher, J. (2017).Trauma-Informed Care: A Sociocultural Perspective. In Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

- Dworkin, E. R., Menon, S. V., Bystrynski, J., & Allen, N. E. (2019).Sexual Assault Victimization Among College Students: A Review of the Literature.Journal of Adolescent Health, 63(1), 24-35.

- Perry, B. D. (2006).Survival Child: A Manual for the Treatment of Trauma in Children and Adolescents.Child Trauma Academy.

- Shapiro, F. (2001).Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing: Basic Principles, Protocols, and Procedures. Guilford Press.

- Ogden, P., Minton, K., & Pain, C. (2006).Trauma and the Body: A Sensorimotor Approach to Psychotherapy. Norton & Company.

- Sachs, E. (2020).The Role of Self-Compassion in Trauma Recovery: A Review of the Literature.International Journal of Trauma and Stress Studies, 2(1), 15-24.

- Duncan, J. (2014). Understanding and Treating Trauma in Children and Adolescents: A Trauma-Informed Approach. Child Welfare, 93(5), 163-181.

One Comment